Melanie claims she is “not a real writer’s writer, except for trying it now.” She is a classical pianist, and piano teacher who has been inspired to write her childhood story by her former piano student, Elizabeth Damewood Gaucher. Forced into really early retirement by the economic crash in 2008-9, this former college music professor now has plenty of time to reflect and write. Oh what a blessing. Melanie is presently trapped in South Carolina, but visits the family in Charleston, West Virginia two or three times a year. She breathes anew whenever she sees the mountains again. Her essay, “Going to the Farm,” recounts memories of trips to the jointly-held family vacation farm in Monroe County, West Virginia, from Charleston. Model-T’s, grand pianos, and wildlife ensue.

Melanie claims she is “not a real writer’s writer, except for trying it now.” She is a classical pianist, and piano teacher who has been inspired to write her childhood story by her former piano student, Elizabeth Damewood Gaucher. Forced into really early retirement by the economic crash in 2008-9, this former college music professor now has plenty of time to reflect and write. Oh what a blessing. Melanie is presently trapped in South Carolina, but visits the family in Charleston, West Virginia two or three times a year. She breathes anew whenever she sees the mountains again. Her essay, “Going to the Farm,” recounts memories of trips to the jointly-held family vacation farm in Monroe County, West Virginia, from Charleston. Model-T’s, grand pianos, and wildlife ensue.

Going to the Farm

It was about 1956-7. I don’t remember exactly because I am now 59 and three-quarters. Most of my memories are smeared right about now in my life.

But my memories about Going to the Farm are spottily some of the most vivid in my pickled memory bank. I remember Mommy packing the red and white vinyl Coca-Cola cooler with ice and snacks for the long (?) trip to the farm, putting them into the backseat of our 1950’s Chevy, two-toned red with a white top.

(I’m the one on the right, presagging belly-button exposure that will of course become popular later in the century.)

We were going rural! We went to the farm every year in hunting season, about October 15 from what I remember. The whole extended family, aunts, uncles, cousins and all would converge for awhile to bond, eat, and for the fellas, do some serious hunting. The big prize might be a turkey for Thanksgiving.

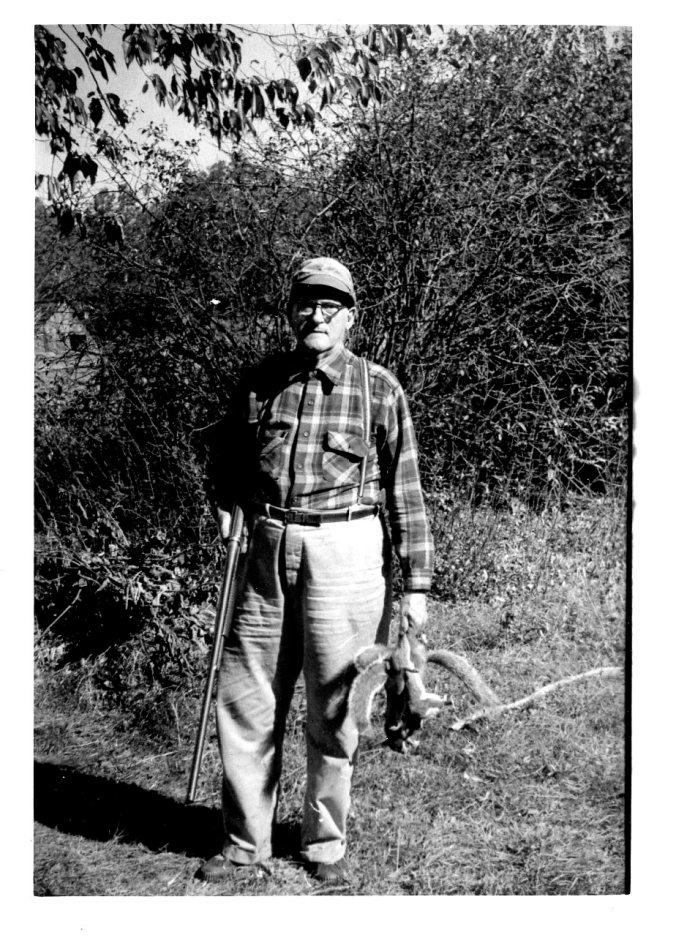

OR maybe a squirrel dinner. That’s Grandaddy there with his gun and three or four squirrel stew ingredients.

Now I get confused because my most memorable trip to the farm was in Granddaddy’s Model-T Ford. I remember him worrying about making it up Pike’s Peak. No, really it was the big uphill grade going to the top of Flat Top Mountain! Chunka-chunka-chunka. We made it. I remember the problems with the “choke” on that Model-T. I’m not sure but I think the West Virginia Turnpike MAY have been there then, newly opened.

We got off of the fancy Turnpike to make our way through Hinton, heading toward Union, passing the beautiful Greenbrier River on the left of the road. Going through Hinton was significant because Grandaddy and his five kids had grown up there during the Depression. Mommy liked to talk about her legs cracking and bleeding into her white socks from the cold as she walked to school. She also told me that Grandaddy set out shots of hot-toddies (Yes, Bourbon) on the stove in the kitchen for all the kids to keep them warm as they walked to school in the morning. This may be why none of the children graduated from college! But he had a job the whole time; He was a conductor on the C&O railroad. They were pretty flush for those times.

Once in Union, it was just a few miles to Gap Mills, population about 50. In Gap Mills, we had friends who kept our Jeep. The Jeep was the only vehicle that could make it up the road to The Farm (except the Model-T; memory confusion remains.) The Jeep was a World War II reclaim, and I have no idea how we got it. Sometimes we stopped at Ralph and Arlene’s for the night to pick up the Jeep and drinking water. I still don’t know how we became friends with Ralph and Arlene, but these things just happen in West Virginia. I’ll never forget the smoky smell of their house (cigarettes and a wood stove combined) and that they had a GRAND PIANO in the living room. I am a piano player. I liked showing off on that old, out-of-tune grand.

The next morning, going from Ralph and Arlene’s house to the farm, we stopped at a house that raised chickens, hence fresh eggs, to supply us for the next few days. That is all I remember about that! But it was about 5 more miles up a dusty road until….

Eventually we turned right onto the dirt, rocky and overgrown road that was the entrance to the farm. The entrance was tough to spot from the main road. There was an iron gate with a padlock on the dirt road, about thirty feet in from the main road. The driver had to unlock the padlock on the gate, and then we were off into the wild! The back of the Jeep was absolutely packed with supplies, and we little cousins were holding onto the top bars of the vehicle, our feet delicately balanced on the bumper. We were actually hanging off the back of the Jeep. Here we go! Get ready for some serious bumps! “Hold on tight!” said the adults who were sitting up front.

Nobody had been up the road for many months, probably since summer time, so the ruts grooved by any bad weather were deep. As we descended into the Rain Forest, the driver had to make sharp left and right juts, avoiding the big pits in the dirt road. I remember flinging right and left off the back of the Jeep as the driver jigged and jagged along the path. Sometimes we had to actually stop and fill in the ruts with brush and stones in order to create a passable road. Sometimes we would stop and pick blackberries on the way in! (But wait: that was the summer trip to the farm. But a vivid memory.)

I think it was about two miles from the main road up the dirt jungle road to the farmhouse, but it took awhile and was always a beautiful adventure. OOH! I just remembered the adults stopping on the way to shoot some pheasants who were in the road. I think we ate them. I know I remember the sound of the flight of the survivor pheasants escaping with their lives. The Jeep persisted.

Once we saw the crosshatch fence, we knew we were just a short downhill jaunt to the farmhouse. The Rain Forest opened up and there was LIGHT ahead and a fabulous cleared hill on the horizon.

We descended the short hill and saw the always sadly neglected foursquare for the first time of this season. (In summer time, we loaded up with an actual lawnmower to knock down the 2-foot tall grass in the yard. In hunting season, I think we just dealt with the leftovers.)

As we went into the farmhouse, “interesting” odors reared their ugly heads. What does a house smell like after five or six months of abandonment? Yes, this is it. Mustiness-wood. But that smell is still a happy memory. None of the wooden walls were painted in the house so all of the open pores of the wood absorbed the scents of nature. A musty memory smell is very vibrant when you are 59 and three-quarters.

We were into the house again, and the first job for the big people was to make sure that there were no snake nests in the beds or in the outhouse. I remember Aunt Gladys finding one in a bed one year. This was very creepy. But my favorite creepy memory is when one of the uncles or aunts found a rattlesnake sitting on the “throne” in the outhouse. Yes. We had to go to the outhouse for those bodily functions. According to legend, someone shot a rattlesnake right between the eyes when we got there one season. The outhouse was a two-seater, by the way. This was pretty much a Cadillac possession for the time. I will spare you the description about sharing this experience with my family members. I remember LYE was involved.

West Virginia Moon by Joe Moss, 1963 *

After checking out the farmhouse and outhouse for varmints, we unloaded the Jeep. It was backed up to the front porch and the big people hauled in all the supplies: Coleman lanterns, water, bags of food, sheets, clothes, ice! Oh ICE! Here comes the memory of getting a huge block of ice somewhere on the trip to put in the ICEBOX. I remember the big metal hook picking up the chunk and placing it into…something for its trip to the farmhouse.

There was no electricity and no fresh water at The Farm. At The Farm, I guess we were just lucky to have a rainwater barrel on the back porch, to be used for cleaning up, ONLY. The barrel was rusty but no matter. The water ran off of the rusty metal roof.

Each family had its own bedroom in the house, except for my little family. We had to share because I was an only child, so we shared with the cousins whose family had too many, I mean FIVE kids. There was a black metal wood stove in every bedroom and a chamber pot for mid-night trinkles. Going to the possibly snakey outhouse in the middle of the night was not an option! Besides, the outhouse was tastefully located about 30 feet from the farmhouse, too far for a mid-night trek. By the way, I remember that the ceramic chamber pot really crisped-up the buttocks in the middle of the night after the wood-burning stove had spent its fuel. My steamy pee was actually a welcome relief from the bitter cold. And, yes, I remember the scent. No. It was a really a smell.

Somehow, the next morning, the Mommies managed to put hot bacon and eggs and cold orange juice on the big table in the dining room. I never thought much about how hard that might have been until now. Where did they get the heat for the bacon and eggs? Why was the orange juice cold, just like at home even though there was no Frigidaire? We were mightily fed before our kiddy outdoor adventures began at The Farm.

Which adventure would be first? We cousins could explore any number of locations on The Farm; We could go visit the Bear Wallow, an ancient cluster of rocks in the middle of the woods, named thusly by the big people because they believed that Black Bears lived in there in the winter time. Of course, that was a scary place to go, but oh so exciting. We always felt very brave when we went there. We could trek through the long grasses up to the top of the “cleared” hill to view the long distance sight of Peter’s Mountain that was VIRGINIA. The mountain was so far away that it was blue.

The Blue Mountains of Virginia.

We could go out on the front porch and watch the older cousins shoot beer cans off of the split-rail fence that surrounded the house. In later years, I would be contributing to this activity with my single-shot 22-caliber gun. I was a pretty good shot, by the way. I killed a lot of beer cans. I wonder now where all of those beer cans came from?

We could go to the little pond that one of my uncles dug, thinking that it would create a lovely lake for our visits to The Farm. Needless to say, the “lake” turned into a mosquito- frog haven right next to the front porch. Brilliant! But the SCIENCE of exploring that murky pond was a creative experience for all us cousins. We spent our pre-teen years with a flashlight out there, shooting the frogs, piling up the little froggie bodies and then blowing up the piles of little froggie bodies with cherry-bombs. Most of my cousins were little boys, needless to say. Why did they (we) do that? I clearly remember dissecting some of those dead froggies with my cousins. It was fascinating. Because of this, I did not have any problems with the grossness factor in Biology class ten years later in high school. I guess you could say that I already knew quite a bit about life versus death.

* * *

Fifty-ish years later, is it any surprise that I now have created a water garden in my backyard that is also flush with rain forest foliage even though I live only two blocks from the center of town? I dug that water garden pond out myself a few years ago. I guess I did not learn any lessons from that dysfunctional uncle. I keep bug spray close as I throw the ball for my darling Golden Retriever because, of course, there is a mosquito problem out there. I bought some tadpoles a few years ago, hoping to create those nightly garumphing sounds that I remember from the froggies at The Farm. They all died. My yard is really trying to look like the woods of The Farm. Because I now live in South Carolina, I do not have West Virginia foliage; I have big sprawling pecan trees, one huge Magnolia, azaleas, very mature Camellias, and on and on. I love my yard because it is the absolute opposite of preened which means that it is beautiful to me.

Now I am 60 instead of 59 and three-quarters at the beginning of this recollection. What have I learned, writing this memoir?

I have learned that it is a blessing that I mostly remember the happy things.

I must have been a happy child because I am still trying to recreate the same scene for my life, fifty years later.

And dear parents, know that the experiences you give your children early in life will live on for them in vivid, Kodachrome colors.

* Read about the famous and controversial painting, West Virginia Moon here.

Cathy is an Ohio gal at heart, particularly so after walkabouts in various other, truly fabulous places. She’s taking advantage of this one wild and precious life by trying new things, which includes this first foray into creative writing (so be gentle). In addition to family and friends, Cathy loves her work supporting entrepreneurs and blogs about it on the

Cathy is an Ohio gal at heart, particularly so after walkabouts in various other, truly fabulous places. She’s taking advantage of this one wild and precious life by trying new things, which includes this first foray into creative writing (so be gentle). In addition to family and friends, Cathy loves her work supporting entrepreneurs and blogs about it on the