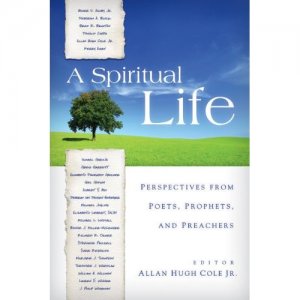

I contributed an essay to the collection, A Spiritual Life, and the advance reviews confirm that the entire book delivers on its promise of engaging a range of meaningful and personal perspectives on spirituality. What does it mean to individuals to live “a spiritual life”?

Writing my essay was a very personal process of articulating the experiences I had after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis twelve years ago. I spent a long time in a state of “unreadiness” to disclose my condition, much of that stemming from fear of the unknown. My spiritual journey propelled me into a braver, stronger, richer place as a child of God. Perhaps one or more of these essays will do the same for you!

I hope you will read the reviewers’ comments below and consider pre-ordering the book for yourself or someone you love. Publication will be in late April 2011.

A Spiritual Life: Perspectives from Poets, Prophets, and Preachers (Westminster John Knox Press), will be published in early 2011.

A Spiritual Life: Perspectives from Poets, Prophets, and Preachers (Westminster John Knox Press), will be published in early 2011.

“Don’t look for a traditional approach to faith or a unified voice in this diverse collection. You can, however, count on graceful prose and an honest, reflective search–and that, I found, was enough to make my own pilgrimage seem more authentic and less lonely.”

Philip Yancey, author of What Good Is God? and Prayer: Does It Make a Difference?

“In A Spiritual Life, Allan Hugh Cole, Jr. has assembled an impressive group of twenty-four “poets, prophets, and preachers” to write about that elusive thing called their spiritual life. What emerges is not a tight and tidy definition of the spiritual life but a glorious topographic collage of the ways in which people infuse their lives with God. These two dozen compelling writers expand not only our notion of the depth and breadth of the spiritual life, but maybe even our understanding of God.”

Sybil MacBeth, author of Praying in Color: Drawing a New Path to God

“Too often Americans think of “spirituality” and “the spiritual life” in ways disconnected from the quotidian challenges of our daily lives. This rich collection offers a powerful and poignant counterwitness, displaying the complexities of engaging God in the midst of the ordinary. You will be stimulated, comforted, and challenged by these wonderfully gifted writers.

L. Gregory Jones, Duke University, author of Embodying Forgiveness

“A spiritual banquet, prepared by some of America’s finest writers and thinkers. If you’re looking for a fresh wind to blow through your life of faith, look no further than this gem of a book.”

Philip Gulley, author of If Grace Is True and the Harmony novels

“These meaty essays, generously spiced with personal stories, provide valuable food for thought about ministry, preaching and everyday life in Christ. What a rich feast! Savor this book.”

Lynne M. Baab, author of Sabbath Keeping and Friending: Real Relationships in a Virtual World

“One of the great gifts of my work is that I often get to ask the question of friends and folks I’ve only just met, “What is God up to in your life?” There are few things I’d rather do than listen to an honest response to that question. Here is a book full of responses by folks who write both honestly and well. Like so many of the folks I’ve listened to face-to-face, these authors give me hope that the Spirit is stirring to bring new life, even in the most unexpected of places.”

Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, author of New Monasticism and The Wisdom of Stability